Caravaggio’s Cupid and the Power of Queer Desire

A personal look at Caravaggio’s Cupid and the queer tension that still shapes how we see his art.

Caravaggio’s Cupid and the Power of Queer Desire

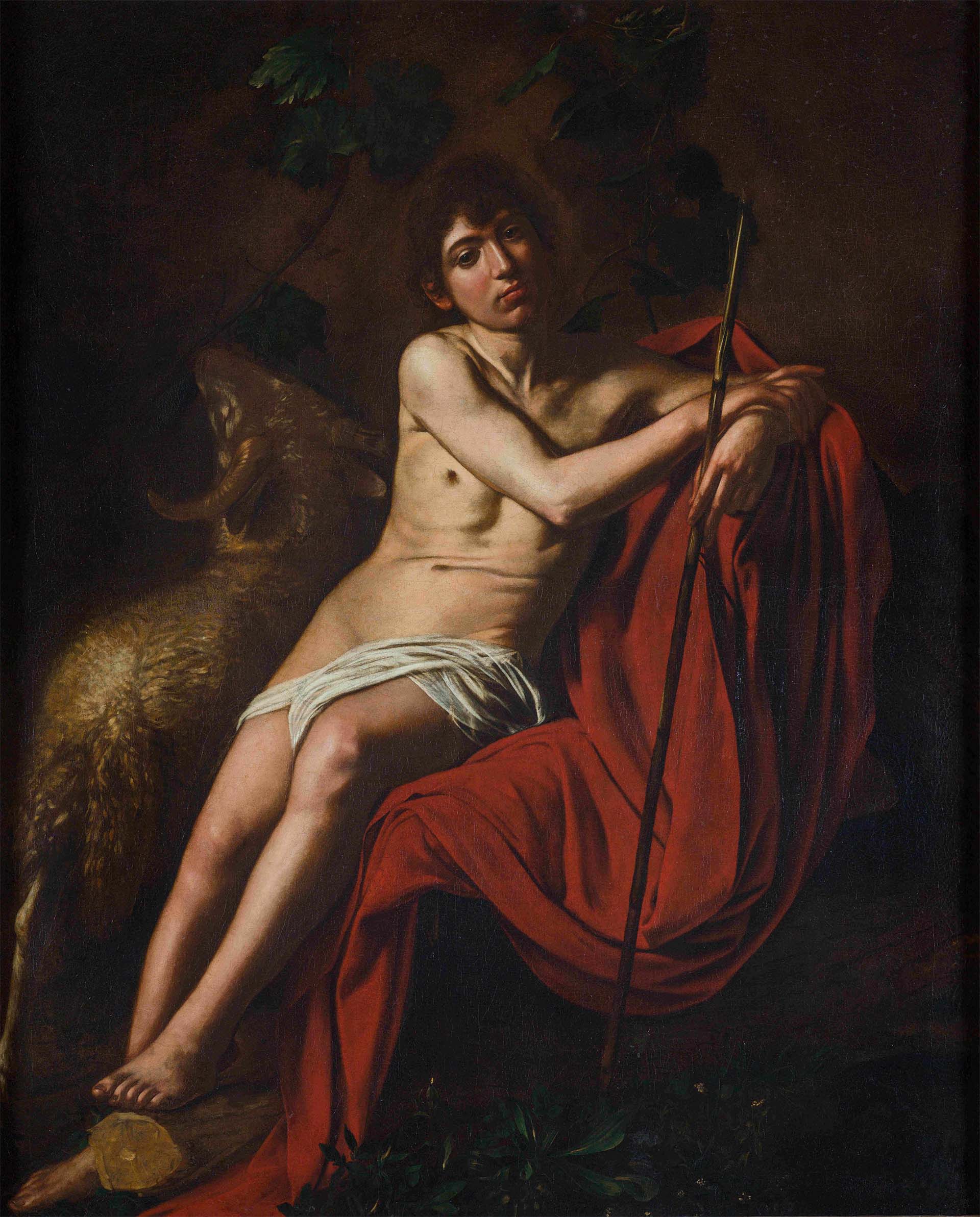

Exhibitions of Caravaggio are always seismic occasions in London, even in a city that lives with three of his paintings in the National Gallery. The loan of a Caravaggio from Berlin’s Gemäldegalerie for a small, single-picture show at the Wallace Collection creates a moment that feels disproportionately rare, and it gives me the reason to return to him. Caravaggio sits in an uneasy place within queer cultural discussion: claimed by some, questioned by others, approached with hesitation yet recognised with an almost disquieting familiarity, a figure who remains historically remote and yet stubbornly, unexpectedly near.

I had already stood before Berlin’s Caravaggio Amor Vincit Omnia, ‘Victorious Cupid’, on my trip to Berlin last year, meeting the painting in the flesh rather than through the distance of photographs, an encounter that still lies very close to the surface of my memory.

%20(1).jpg)

London holds its own piece of this story. The National Gallery shows Boy Bitten by a Lizard, an early painting often read as a warning wrapped in pleasure. I first saw it long before Berlin, long before I knew why it unsettled me. His work keeps returning to the present. Even with centuries of study, we still feel the pull of what we cannot fully know about him.

A second viewing of Victorious Cupid came in a little over six months, now commanding its own exhibition simply titled ‘Caravaggio’s Cupid’ in the basement gallery of London’s Wallace Collection, a key space for major Caravaggio exhibitions.

This boy appears across several of Caravaggio’s works from those years. His face shifts from playful to fearful, and you feel the artist returning to him again and again.

So, what is my relationship with Caravaggio as an artist myself? And how has his Cupid’s arrow struck me with such shattering precision?

In 1986 Derek Jarman turned my 18 year old head toward the Italian Baroque, seventeenth century painter with his reimagined biographical movie, Caravaggio. It was a time of fear. AIDS was killing us. Britain was two years away from section 28 and homophobia was thriving through right wing media and every area of public life. These were the Thatcher years in the UK. A particular attack affecting the arts was made public in the press coverage of MP Winston Churchill’s efforts to extend the obscene publications act to include two of Jarman’s films.

The struggle was brutal. And I was afraid.

Venturing from my home in SE London into the metropolitan anonymity of London’s South Bank and the National Film Theatre gave my latent artist and sexual identities a precious space to feel the presence of community. Jarman went on to say Caravaggio’s age was in many ways more open than ours was.

The Catholic world was more complex than people think. Public morality was harsh, yet private life was often left to the individual. Sin was a matter for the church, not the state.

Caravaggio painted in a city ruled by faith and punishment, yet desire and danger moved through daily life in quiet ways.

To me, Caravaggio’s use of chiaroscuro is a powerfully seductive aesthetic, and his use of the darkest pigments suggests a psychological sense of being, the undercurrent of the diasporic experience. It is the interior world of gay subversive men’s navigation of desire, fear and power. And our exterior world of forbidden excess.

My response to Caravaggio is about resonance with his psychological method. The intensity, the darkness, his unflinching mirroring of the human condition suggested in his paintings feels intimately familiar. He guides my attention to the beauty of gestures that reveal the hidden inner world.

Many believe the model was Cecco, a figure now widely discussed in queer art history, the young apprentice who lived and worked in Caravaggio’s home. His presence ties these paintings together and gives them a personal pulse.

Caravaggio’s Cupid works on two levels and remains central to LGBTQ art conversations, the visible and the coded. Both reveal incredible beauty. To the gay male gaze the painting is bright with subtext. The ancient god boy scatters the pillars of a Eurocentric civilisation.

For the likes of me, whose identity weaves Blackness, gayness, diaspora, leather and a sculptor’s eye for the figure, Cupid becomes a mirror. It reflects the coded ways gay men have always communicated, through gesture, ambiguity, silence and a way of looking. Cupid’s beauty is startling. The grin, the nakedness, the dark feather brushing the thigh. But coded messages abound and hit between the ribs. Cupid’s tension lies between innocence and mastery situated in one pagan body.

Cupid touched multiple threads of my identity at once. What overwhelmed me, what made my heart race uncontrollably, is that Cupid lives in the very space contemporary art should live, the intersection of beauty and desire, fear, danger and defiance, body and code and a political clarity of mind.

Cupid stands in that charged space where beauty, desire and danger meet. That is why the painting hits with such force.

It is on public display at the Wallace Collection in London until 12 April 2026.

Get weekly updates

.png)

Join Our Newsletter

Get a weekly selection of curated articles from our editorial team.

.svg)